I am positive that every scenic designer in the U.S. reading this blog understands the drill:

- Carefully read the script.

- Discuss it with the director.

- Do your research.

- Take time to conceptualize.

- Repeat.

The process involves engaging in these steps again and again in a cycle, winding your way inward towards [what we hope is] the ideal scenic design for the production. Once the precious ideal design is realized (or time runs down and out)(whichever happens first), we freeze the design, and hand it over to the technical director. Their job is to determine how to make the design a reality.

Of course, other factors become important once you get out of the classroom where this process is taught and learned. Budget is one very important factor. So is build time. And another important factor are the skills of the people who will actually build what’s been designed. As you create your scenic design, you learn to play to the strengths of the shop you work with, rather than the shop you would like to have.

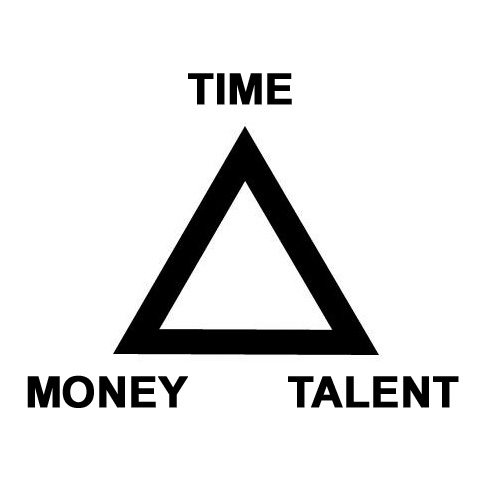

The Equation: Time, Money, and Talent

One of my old professors use to call this the Time-Money-Talent triangle. I was taught this as a part of advanced stagecraft and technical direction. The idea is that in any production, you can do without one of these three things, but never without at least two.

One of my old professors use to call this the Time-Money-Talent triangle. I was taught this as a part of advanced stagecraft and technical direction. The idea is that in any production, you can do without one of these three things, but never without at least two.

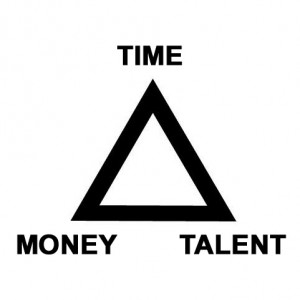

If you are lacking in one of the three, you can compensate by increasing the others. A quicker way to say this is: “Fast, Cheap, Good. Pick two.”

In the classroom, when I teach design I start with this definition:

“Designing is finding the best solution to a problem within a given set of circumstances.”

Those circumstances include some basic considerations. What does the director want to do with the show and the set? What’s required by the actors for them to be successful? What are the requirements in the script? A major factor is the venue, as is the type of audience you anticipate attending the production (age, expectation, culture, etc).

After those considerations, toss in the Time-Money-Talent triangle. Finding a single solution to everything can be like trying to win a chess tournament. Most importantly, its important to realize that this is not only an engineering or a financial challenge; the solution we discover has to be beautiful, too.

Often when we teach, most of these important factors are downplayed at first. Drafting, drawing, and conceptualizing can be hard enough for the design student engaged in their first design, without everything else. The typical second-year college student might have a conniption if you asked them to solve all of these challenges at once. That’s why we begin with the pure design process, and gradually introduce the other challenges later.

This order has become ingrained in our industry. Our ideal process is one of pure collaboration between the designer, the director, and the playwright. Seasoned artists learn to embrace the constraints of time, money, talent, etc., but developing artists often feel that their vision is being compromised.

“Compromise” is a very ugly word for beginning artists. We don’t want to compromise our vision, that thing that makes what we’ve come up with unique. This is true for designers, directors, and every other artist involved in the theatrical process. A seasoned, fantastic production team knows that if the collaboration is on target, nobody compromises. Instead of anyone giving up what they see as the essence of their vision, they can discover a solution that satisfies the essential nature of everyone’s artistic vision. If theatre is about artists collaborating, then the result of good collaboration is greater than the sum of its parts.

That’s a great idea when we are discussing satisfying the director and the script. But what do we do about all of those other challenges? How do you deal with the budget? What about that godawful space we have to design in?

Embracing and Owning What We Have

At the start, when students begin learning these steps, directors and designers need to be able to embrace and own the resources with which they will be working. Instead of always developing an ideal that may or may not be achievable, they need to have a second method of designing in their toolbox, one that is every bit as strong (or stronger) than the purist method. I say directors and designers, because they need to learn this process together.

At the start, when students begin learning these steps, directors and designers need to be able to embrace and own the resources with which they will be working. Instead of always developing an ideal that may or may not be achievable, they need to have a second method of designing in their toolbox, one that is every bit as strong (or stronger) than the purist method. I say directors and designers, because they need to learn this process together.

A Mistake We All Make

A mistake we all make when we begin our design careers is to create on paper what we want, then force available resources into that form. This will usually lead to failure. Instead, when the process starts, the director and the designer can look at things differently by surveying the venue, considering everything that is on-hand, and allowing themselves the freedom to be inspired by it. “Look at this curving staircase . . . wouldn’t it be interesting if it just went up to nothing, in the middle of the stage?” “We have about 150 of these short plastic tubes . . . you know, we could stage an entire dance around that.” We do our students an artistic and practical injustice if we do not teach them more than one process.

In various parts of the globe, the design process is not radically different, but the formulated, narrowly prescribed version I started this blog with is a very American way of doing things. Because Europe has so many languages, cultures, and nations all pressed together, there is a less quantified method of producing a design there. You tend to encounter more overlap between design areas, and more overlap between design and architecture, or theatre with other disciplines. The process itself is not so specifically defined as it is in the U.S. In Europe, it is more common to engage in a different process each time, with results being innovative, surprising, and revealing.

Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space

In 2011, I had the opportunity to be at the Prague Quadrennial. It’s full name is the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space. It is a hugely important event for scenography, emphasizing design for many disciplines. Areas included are costume, scenery, lighting, multi-media, and theatre architecture. Every variety of performing arts is represented. From around the globe, you find artists and designers coming together for this exciting event. It’s a combination festival, competition, and conference. Included among everything else, and there is a lot, is an international exhibit with unique installations designed and produced by dozens of different countries.

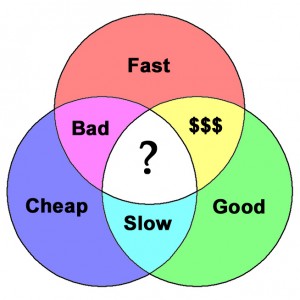

Prague Quadrennial Installation: Art from Nothing, by Danish Children’s Theatre

In 2011, these installations were all featured at the Veletržní Palace, a massive museum of modern and contempary art with generous exhibit halls. In this space, I viewed the Danish Children’s Theatre exhibit Art from Nothing. It was composed of one material- cardboard. Above and beyond all else, this was my favorite installation. It was surrounded by installations from other countries, including China and the United States, both of whom contributed very elaborate, highly polished, and expertly manufactured installations.

In 2011, these installations were all featured at the Veletržní Palace, a massive museum of modern and contempary art with generous exhibit halls. In this space, I viewed the Danish Children’s Theatre exhibit Art from Nothing. It was composed of one material- cardboard. Above and beyond all else, this was my favorite installation. It was surrounded by installations from other countries, including China and the United States, both of whom contributed very elaborate, highly polished, and expertly manufactured installations.

What struck me about Art from Nothing was not that they were able to create so many things, all of the elements, out of cardboard. It’s that they took their total lack of materials and made it into a positive by creating something that was pure spectacle. Nothing about the installation looked as if they were simply “making do” or trying to “get by.” Instead it was simultaneously a celebration of cardboard and creativity. It was about having nothing to work with and needing nothing to work with. It was liberating to experience Art from Nothing. Question: ”What do we need to put this show up?” Answer: ”Nothing.”

Random Item

Random Item