In the spring of 2014, I was working as a guest designer at Auburn, University in Alabama. As a part of a fairly casual conversation during a work-call onstage, an undergraduate set-design student by the name of Sarah asked me a very simple question: “How did you get started as a Set Designer?”

Are you ready?

When I was an undergrad at Indiana-Purdue University in Fort Wayne, Indiana, I made myself available to high schools and small community theatres in about a 45 minute radius around myself. I designed and built the sets that I designed, and served as my own electrics crew, depending on what I had been hired to do. This was from about 1988 though 1992. I would typically charge between $300 and $500. That was a lot of work for a little money, even back then.

I talked about this briefly with Sarah while we worked on the set. In her opinion, she did not feel that she was “ready” to design yet. This struck me as a rather odd thing for her to believe. I don’t know her well, but even working with her for just a few days, it was obvious that she is motivated, intelligent, and informed about what is what on a stage. I know the program at Auburn University as well, and even a sophomore or junior in their program would have a lot to offer a small theatre as a freelancer.

I continued to think about this while I worked.

Not ready for everything, but ready for some things.

In academia, there are a lot of standards that need to be met. In my program, we conduct annual juries of all majors to evaluate where they stand in their training. In classes, there are rubrics and syllabi that tell everyone what they need to do to meet expectations. There are course catalogs that tell students when they have completed their minor and their degree.

By placing design for theatre into a university structure, it becomes very easy for students to feel like there is some specific tipping point after which they will official be “ready” to design for theatre.

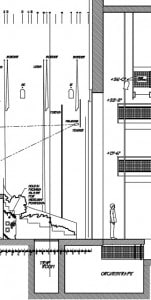

In a university environment, we are preparing students to work in a professional environment. Though professional environments can vary (a lot), there’s a pretty clear list of skills and abilities that need to be covered. Set designers, for example, need to know how to produce a complete design package (plates of drafting, renderings or models, storyboards as necessary, etc.), and also know how to work effectively in a collaborative production environment.

Students know this, and this colors their imagination as to what they are ready for. Here are some reality-checks to keep in mind.

A lot of theatres out there would be really happy to have you at just the level you are at.

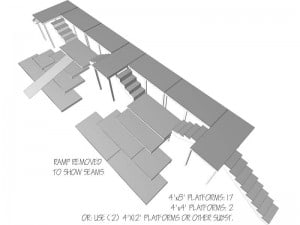

Many theatres don’t have a technical director. Or a technical staff. There are small community theatres that have a small stock of set pieces and platforms, and maybe even a small shop, but no formal employees. Just having someone who knows what’s what backstage, who is willing to put something respectable together, and work well with the director, might be worth more to them than you can imagine.

High School Theatre Programs

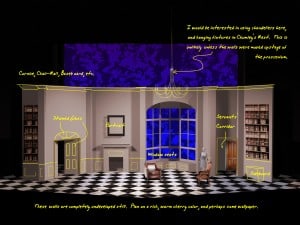

High schools are the most common example of this arrangement. They usually have a decent stock of flats and set pieces. They rarely have one person acting as a technical director, and almost never have an actual designer on hand. High school drama directors do too many jobs. They often serve as the director, choreographer, design staff, and technical staff, not to mention doing most of the real duties of the stage manager. Demonstrate to a few schools in your area that you can

- Show them what the set will be before you start building.

- Work with their existing stock plus a modest budget.

- Have it built for them on time.

- Do all of this without over-extending your own availability or their resources.

- Make these items your priority. Do not try too hard to turn them into a “real” theatre; just make their show the best it can be with minimum stress.

You will be enormously popular. You will be hired back. You will be referred. Your resume and your skills will grow.

“I’m going to be” vs. “I am.”

“I’m going to be an actor.” “I’m going to be a lighting designer.” “I’m going to be a dancer.” “I’m going to be a Technical Director.” Early in our careers, in all of our fields, we all recite something like this to ourselves over and over and over.

“I’m going to be an actor.” “I’m going to be a lighting designer.” “I’m going to be a dancer.” “I’m going to be a Technical Director.” Early in our careers, in all of our fields, we all recite something like this to ourselves over and over and over.

Own your career. Right now. “I AM a designer.” No more stalling. No more safety nets.

This does not mean you are ready for anything. Nobody is. Every designer has strengths and weaknesses, personal style, and a few niches that they fill best.

You probably have a long and interesting career in front of you. You have lots of time to develop in a lot of directions. But in the meantime, your career already started. There are plenty of niches that suit your design skill right now. Fill them.

How do you become a videographer? You tell people that you are a videographer. Convince someone to hire you. Do a good job. Repeat. The same formula is true for set designers. You don’t have to have a degree. You just have to have the guts to tell people that you can do it, and then make it happen. You don’t need a college degree to be a set designer. You are studying in college to become a better set designer.

Mix it Up

Don’t embed yourself too deeply in beginner design work. You can serve yourself and your art quite well doing that, but be careful not to become an expert at working with very little. Broaden your skills and abilities, too.

Don’t embed yourself too deeply in beginner design work. You can serve yourself and your art quite well doing that, but be careful not to become an expert at working with very little. Broaden your skills and abilities, too.

Work at your college or university as much as possible as a painter, a carpenter, a stitcher, whatever. Do summer-stock theatre. Work at your regional performing arts center. Go to conferences. Keep exposing yourself to higher levels of skill so that you grow quickly. Design for the small theatre, work hourly at the big theatre, and hop back and forth. You’ll find the small theatres hiring you start to get bigger, and so does your staff position at the arts center.

Incumbency

In my experience, this is something that applies more to Set Design than any other kind of design in theatre.

In my experience, this is something that applies more to Set Design than any other kind of design in theatre.

Directors and theatre companies have a tendency to find a set designer or two that they are comfortable working with, and they stick with those people, sometimes for many years.

You get used to the venue as a set designer, and you learn how to work it well. You get used to what the budgets are, and you learn what sort of materials are going to be readily available locally; even though you usually aren’t building the set, you tend to take this sort of thing into account. You get used to the stock. Over time, the storage areas become filled up with things that you designed in the first place, so you already know the exact dimensions of almost everything in stock.

You get close to directors, too. You learn how they work and think. You know from experience what will and won’t work for them on stage. You can get very efficient working with directors that you know well. The result is that set designers often become glued to specific theatres or specific directors.

If you are just starting out in a given area, you might find that there are few opportunities for you as a set designer at the skill level you should be working at. You have to be a little patient.

Have a secondary emphasis or two that will serve you as well. These might include technical direction, lighting design, costume design, painting, props, etc. Don’t let anyone forget that you are a set designer. In the meantime, though, be pleasant and easy to work with. Things sometimes change very quickly.

Random Item

Random Item